Happy Moltmann Monday! Today’s selection comes from Ethics of Hope, which, if you didn’t know, is a more recent addition to Moltmann’s canon of books and a pretty readable one at that. If you’re looking for an overview of his theology related to contemporary issues, this is a good pick. I’m sharing a section from his chapter entitled “The Time of the Earth.” He’s talking about creation and process and evolution.

Are we right to start like Darwin from a ‘war of nature’ and a continual ‘struggle for existence’, or is it more appropriate to start from cooperation as the principle of evolution, and mutual recognition as the principle of humanity? As we know, Darwin’s ‘struggle for existence” interpretation was exploited by the so-called social and racist Darwinists. But according to more recent research, in the build-up of complex systems of life in the evolution of nature, the principle of co-operation is more successful than the principle of competition…

…The new neurology of Joachim Bauer shows us that the genetic disposition of human beings is regulated by their motivation system. But our motivation system is stimulated and enlivened by the acceptance, recognition, appreciation and esteem of other people. Rejection, depreciation, isolation and existential fear weakens it, and in the extreme cases eliminates it altogether. The fight of all against all makes human beings lonely. ‘United we stand, divided we fall,’ said Patrick Henry during the American Revolution, and that is a general truth…

These new biological perceptions confirm in their own way the Christian doctrine of justification: ‘receive one another as Christ has received you for the glory of God.’ The unconditional acceptance by God- in spite of all unacceptability, as Paul Tillich added- is the heart of the Christian experience of God and is the eternal ground for self-respect and neighborly love.

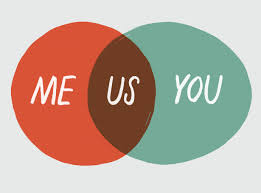

So. This idea that cooperation and not competition is at the bottom of things in this universe is one of my deepest held beliefs. You can see it as a sort of invisible thread through all of Moltmann’s works, though he hardly speaks so on the nose about it. But isn’t this one of the reasons he has such a flat ecclesiology? (fancy word for the way he thinks we should organize church structures) We are not in competition with each other, church people. We are all here to work together. Maybe our differences even allow us to do this better in some cases. This is why Moltmann can talk with integrity about interfaith work, and cross-cultural theology, and all kinds of topics that have the potential to keep us apart from each other. He does that because he doesn’t believe we are meant to be apart like that. It is fundamental to the way he sees God, and human flourishing. I remember also the first time I stumbled onto the work of Meg Wheatley, who vehemently adopts a cooperative view of the world. Consequently she is one of the only leadership “experts” I can bear to read without constant groans and eye-rolls. Whether you’re a leader or not, if this is hard for you, I highly suggest you read her stuff and catch the rhythm of cooperation she plays in the pages of her work.

Here is where the rubber meets the road: if you spend your whole life thinking you are struggling against everyone and everything else, I’m not sure where you leave room for grace. How do you experience it, much less give it, when you are so wrapped up in these ideas of war and struggle and competition and scarcity? You just cannot. You are a hamster on a wheel, friend, and there’s no way out unless you get off altogether.

I love that Moltmann connects this to justification. I don’t know about you, but that word just lies flat for me most of the time, hammered as it has been by so many long-winded and boring theological treatises. UGH. WHO CARES? I wonder in my lesser moments. But it’s so important. There is something lovely in that word, if we could find our way into it. And what it means is this: we have been unconditionally accepted by God, despite, as Tillich puts it so well, our unacceptability. God has invited us and also received us when we have come, in whatever tattered and sad little condition we’ve wandered up to that door. We did not have to beat anyone else to the front porch or prove ourselves better than anyone else to get through the doorway. God’s love does not run out.

When we fight against all, we are lonely. How else could we be, if we think it’s us versus the world? We become divided from everyone and everything else, until we are finally divided in our own selves, too. Friends, this isn’t the gospel good news, or the soulfulness of our human experience.

To find our way back, we walk the road of cooperation. We realize how connected we are. We ponder with amazement that we have been received by nothing short of the miraculous glory of God. We begin to realize God has enough love to go around, and then, wonder of wonders, we start acting like we might, too. We find we have room for empathy, and pardon, and understanding, and even passion enough for justice and peacemaking. All because we draw from the well of justification, which holds the waters of cooperation, which is at the heart of the nature of God.

Danielle, I read this timely message and can’t help but remember Rachel Held Evans’ mantra for us continually envious writers at the Buechner workshop: “We serve at the pleasure of a generous Master. There is plenty of work to do.” I’ve actually been using this to calm myself down when confronted with “everyone else’s” success. Thank you for another great piece.

Thinking about this for tomorrow’s sermon about growing up. xo