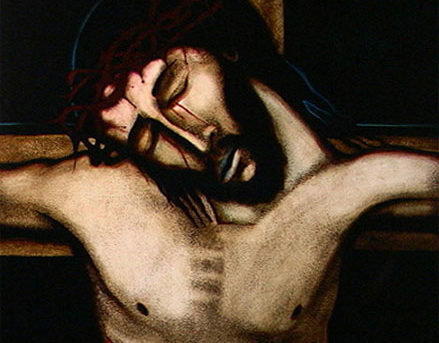

As we are in the season of Lent, I wanted to bring you this paragraph from my favorite book, The Crucified God. It’s from his chapter entitled “Resistance of the Cross Against Its Interpretations” which may be my favorite chapter of the book because it remains so prophetic and necessary:

The religions and humanist world which surrounded Christianity from the very first despised the cross, because this dehumanized Christ represented a contradiction to all ideas of God, and of man as divine. Yet even in historic Christianity the bitterness of the cross was not maintained in the recollection of believers or in the reality presented by the church. There were times of persecution and times of reformation, in which the crucified Christ was to some extent experienced as directly present. In historic Christianity there was also the ‘religion of the suppressed’ (Laternari), who knew that their faith brought them into spontaneous fellowship with the suffering Christ. But the more the church of the crucified Christ became the prevailing religion of society, and set about satisfying the personal and public needs of this society, the more it left the cross behind it, and gilded the cross with the expectations and ideas of salvation.

And then Moltmann quotes H.J. Iwand, who said this doozy of a sentence:

We have made the bitterness of the cross, the revelation of God in the cross of Jesus Christ, tolerable to ourselves by learning to understand it as a necessity for the process of salvation…As a result the cross loses its arbitrary and incomprehensible character.

If you have seventy-eight alarm bells going off in your head after reading that, let me begin by saying this: Moltmann (and Iwand) do not mean to say that the cross has nothing to do with salvation, or that the cross isn’t deeply and intentionally tied up in God’s act of salvation in Jesus. What they are trying to say is that it’s worth considering how we have so simplified the cross that it has become nothing more than a convenient solution to our rather basic salvation math problem. And the reason that’s problematic is because a) salvation is a lot more complicated than that and b) the cross means a whole lot more than that.

When we choose to see the cross only as a means of fulfilling our personal salvation needs, we sidestep all the things that make the cross difficult, uncomfortable, scandalous, and incomprehensible. Rather than squirming, we decide instead to ignore, to personalize, and to sentimentalize it.

So maybe what you need to give up for Lent (other than original sin, which you won’t miss one bit, I promise) is the idea that the cross only means you are saved from sin. Consider what it might mean that your interpretation of the cross is a burden on it, rather than a reflection of it.

What would it look like for you to allow yourself to be scandalized by the cross?

Moltmann’s point is that there is much about the cross that is and that will always be a little bit despicable to us, and our faithfulness as Christians is not to reject it but to accept that as part of what makes the cross such a transformative act. Jesus was stripped of both his humanity and his divinity on the cross. He was left for dead. He was an enemy of the state, an enemy of organized religion, an enemy of the status quo, an enemy of just deserts. He was above all- and this is important- the enemy of death and destruction, which throws some rather serious shade on all the other things that got tangled up in his own condemnation on the cross, because it assumes that they were in some way, too.

Which brings us back to the sentence in bold above: The more the church of the crucified Christ became the prevailing religion of society, and set about satisfying the personal and public needs of this society, the more it left the cross behind it, and gilded the cross with the expectations and ideas of salvation.

The American church is not the church of the crucified Christ. It is not, and it never has been. It is the prevailing religion of society, and its central desire is to satisfy the personal and public needs of that society and to support in any number of ways its own survival. And because it continues to choose that path, it continues to leave the cross farther and farther behind it. American Christianity has decided to burden the cross with only one thing, to the exclusion of all else: our own misguided expectations and ideas of salvation. By doing so, we have made the cross tolerable (how else could we have cotton blankets with crosses on it or blinged out cross jewelry and shirts or cute little ceramic crosses hanging in our kitchens) but we have also made it cheap, and shallow, and rather empty.

Which is why I will never stop being grateful that the cross has this unfathomable, magical way of resisting our bad interpretations of it. The facts are the facts, and no amount of cross-encrusted coffee mugs are going to take away from the fact that an innocent Jewish man born to a refugee family who we profess to be the son of God was condemned, beaten and executed as an enemy of the state and an enemy of organized religion and that even his own followers abandoned him because they could not bear to see it happen.

And apparently neither can we.

The very first sentence of this book, which is a sentence that literally saved my faith, is this: The cross is not and cannot be loved. This Lent, consider letting go of your need to love the cross for what you think it gives you. Look on it instead, in all its complicated, confusing, facets, and allow it to destabilize you. Allow yourself to be brought into Christ’s suffering rather than doing everything you can to avoid it. See what happens when you stop burdening the cross with your own salvation, and see it as the salvation of God for the life of the world instead.

I cherish these words! Thanks